SAIs and Climate Change Adaptation

[cmsmasters_row data_shortcode_id=”37vf6gxyb” data_width=”boxed” data_padding_left=”3″ data_padding_right=”3″ data_top_style=”default” data_bot_style=”default” data_color=”default” data_bg_position=”top center” data_bg_repeat=”no-repeat” data_bg_attachment=”scroll” data_bg_size=”cover” data_bg_parallax_ratio=”0.5″ data_padding_top=”0″ data_padding_bottom=”50″ data_padding_top_laptop=”0″ data_padding_bottom_laptop=”0″ data_padding_top_tablet=”0″ data_padding_bottom_tablet=”0″ data_padding_top_mobile_h=”0″ data_padding_bottom_mobile_h=”0″ data_padding_top_mobile_v=”0″ data_padding_bottom_mobile_v=”0″][cmsmasters_column data_width=”1/1″ data_shortcode_id=”tem2ks9ksr” data_bg_position=”top center” data_bg_repeat=”no-repeat” data_bg_attachment=”scroll” data_bg_size=”cover” data_border_style=”default” data_animation_delay=”0″][cmsmasters_image shortcode_id=”i01zint6cr” align=”center” animation_delay=”0″]15506|http://146.66.97.177/~intosaij/site/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/SAIs-and-Climate-Change-Adaptation-360×360.png|cmsmasters-square-thumb[/cmsmasters_image][/cmsmasters_column][/cmsmasters_row][cmsmasters_row][cmsmasters_column data_width=”1/1″][cmsmasters_text]

by Michelle R. Wong (United States Government Accountability Office) and Willemien Roenhorst (Netherlands Court of Audit)

Climate change is considered, by many, to be a complex, crosscutting issue that poses risks to several environmental and economic systems. According to the National Research Council of the United States, although exact details cannot be predicted with certainty, there is a clear scientific understanding that climate change presents serious consequences to human society and many of the physical and ecological systems upon which it depends. Climate change adaptation (adaptation)—adjusting to natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climate change—is an important part of managing these risks.

Despite adaptation’s role in managing climate change risks, a 2012 audit from the European Organization of Supreme Audit Institution’s (EUROSAI) Working Group on Environmental Auditing (WGEA) found that adaptation is not a priority among the eight European governments included in the audit.1 Most of these governments developed risk and vulnerability assessments to gather information about climate change impacts, but only two of them had developed a comprehensive adaptation strategy. Very few governments had initiated actions or assessed future climate change implications for their national economies. Measures implemented were largely in response to current climatic challenges and were not initiated to adapt to anticipated medium- or long-term climate change impacts.

Adaptation is becoming an increasingly important subject for Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) as climate change impacts pose financial risks to governments. For example, over the last decade, the U.S. government incurred over $300 billion in costs due to extreme weather and fire (as reported in the president’s 2016 budget request). In addition, the National Academies of the United States believes costs are expected to increase as rare weather events become more common and intense due to climate change. The SAIs of the Netherlands and United States have conducted audits on adaptation for a number of years. This article provides an overview of the frameworks used for these audits, outcomes and impacts of this work, and challenges SAIs may encounter. These examples show that adaptation can be audited by SAIs in various ways and that such audits can have positive impacts.

THE AUDIT FRAMEWORK

The SAI of the Netherlands (Netherlands Court of Audit or NCA) conducted an audit in 2012 at the request of EUROSAI WGEA to take part in a coordinated audit of adaptation.2 From a national perspective, this audit was relevant due to the issue’s significant social importance and international agreements to which the Netherlands has committed, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In addition, previous NCA audits found that government expenditures on climate policy could strain future public finances. The NCA examined the 2007 Dutch climate adaptation policy, specifically with a focus on:

- Assessments of risks and vulnerabilities at the national level (see Figure 1);

- Setup, coordination and monitoring of the national adaptation policy;

- Financial aspects (i.e., expenditures, costs, benefits).

This framework reflects a comprehensive audit approach designed to provide insight into the organization and progress of the national adaptation policy.

Over the years, the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) has issued several reports on adaptation. Based on this body of work, in 2013 GAO added “Limiting the [U.S.] Federal Government’s Fiscal Exposure by Better Managing Climate Change Risks” to its High Risk List, which calls attention to U.S. agencies and program areas that are considered high risk due to vulnerabilities, such as fraud, waste, abuse, mismanagement or being most in need of transformation. In particular, GAO identified areas where U.S. government-wide improvement is critical to reduce fiscal exposure, creating a framework for conducting audits of adaptation. These areas include, but are not limited to, the U.S. government’s role as:

1. Leader of a strategic plan that coordinates federal efforts and also informs state, local and private-sector action;

2. Owner or operator of extensive infrastructure;

3. Insurer of property and crops vulnerable to climate impacts;

4. Provider of data and technical assistance to various decision makers responsible for managing the impacts of climate change on their activities; and

5. Provider of disaster relief.

In February 2017, GAO issued an update to its High Risk List and determined that the federal government has made some progress on this issue but has not met all of the criteria for removal from the list.3

CHALLENGES

SAIs are well-suited to audit adaptation. Climate change is a cross-cutting issue, and many SAIs are mandated to review a range of policy fields to enhance government functions. However, SAIs could face certain challenges when auditing adaptation efforts, including:

Uncertainty. Adaptation attempts to address a complex and long-term problem with impacts that may emerge gradually with varying levels of uncertainty. As such, auditors should keep the long-term, evolving nature of adaptation in mind during audits and when formulating conclusions and recommendations, which the NCA did in its 2012 audit. The NCA concluded, among other things, that successive governments did not have a full understanding of the risks presented by climate change in a number of areas and had limited awareness on how these risks potentially interacted. As a result, NCA recommended governments periodically analyze climate change risks and vulnerabilities in all policy sectors, then integrate and evaluate the results of these analyses so that comprehensive, government-wide decisions can be taken, as needed, to revise climate adaptation policy.

Local, regional, and global dimensions of adaptation. It is important for auditors to be aware that potential climate change impacts in a specific country can affect other regions of the world and across sectors.4 For example, according to a study commissioned by the U.S. General Services Administration, a single climate-related event can have compound effects, with a range of direct and indirect impacts, across sectors. According to the study, these effects were demonstrated in 2011 when severe flooding disrupted electronics manufacturing in Thailand, leading to delays and disruptions to companies around the world. At the time of the flood, 45 percent of the world’s computer hard drives were manufactured in Thailand. Despite the regional nature of climate change impacts, auditors should be aware that adaptation efforts are usually country- and location-specific. Each country and location has its own adaptation needs and resources, which can make it difficult to compare efforts across countries. However, SAIs can still learn from other countries’ practices. For example, as part of a 2015 review of U.S. federal efforts to provide climate information, GAO studied how Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom used climate information systems to provide lessons learned for developing a U.S. national climate information system.5

Appropriate criteria. Criteria exist that can be used or tailored for adaptation audits, even though this is a relatively new field. As an example, the 2012 NCA audit criteria were derived mainly from (inter)national agreements the Netherlands signed (e.g., UNFCCC) and the 2010 standards set by the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI) WGEA in “Auditing the Government Response to Climate Change: Guidance for Supreme Audit Institutions.”6 INTOSAI also provides basic standards on good governance, such as clear allocation of responsibilities to public actors involved in policy. GAO has used a variety of criteria, including “Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government,”7 internal agency guidance, and Presidential Executive Orders that direct certain agencies in execution of laws or policies.

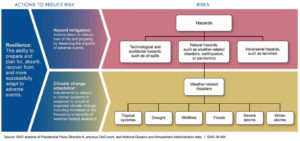

Terminology. Although a newer field, adaptation is related to concepts familiar to SAIs, such as risk management, resilience and hazard mitigation, as GAO illustrated in May 2016 (see Figure 2).8 Therefore, SAIs are able to use similar terminology when auditing adaptation.

AUDITS WITH IMPACT

SAIs can audit adaptation to enhance government practices and develop potential cost savings, despite the uncertainty and complexity of climate change. In 2014, GAO found that rising growth and property values in hazard-prone areas has increased losses, and that climate change may compound this effect. Data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Risk Management Agency (RMA) showed that exposure to potential insured property losses grew by 8 percent, from $1.3 trillion in 2007 to $1.4 trillion in 2013.9 GAO recommended that FEMA and RMA take steps to encourage flood and crop insurance policyholders to adopt practices that reduce long-term risk and federal exposure to losses. FEMA agreed with GAO’s recommendation, while RMA neither agreed nor disagreed. In another instance, in 2015, GAO found that few selected U.S. federal agencies had implemented actions to manage climate-related risks to federal supply chains—which transported roughly $445 billion in goods and services in fiscal year 2014—in part due to being in early stages of planning and not fully identifying these risks.10 GAO concluded that, not knowing the potential risks means U.S. agencies are not well-positioned to identify or implement actions to manage these risks, which could compromise missions and stretch limited resources. To help U.S. agencies manage these risks, GAO recommended the U.S. Council on Environmental Quality clarify its guidance on including supply chain risks in agency adaptation plans and develop a plan for convening an interagency working group on supply chain climate vulnerability. The Council agreed and implemented GAO’s recommendations within a year of the report. In addition, one of NCA’s main 2012 recommendations was that the government should soon implement a national climate adaptation program consisting of a coherent package of actions, projects, and activities, and cover all policy fields requiring adaptation to climate change. Since 2012, the Dutch government has addressed all of the report’s recommendations. In December 2016, the cabinet presented a new National Climate Adaptation Strategy to Parliament, aimed at making the Netherlands climate resilient in all sectors.

1EUROSAI Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Adaptation to Climate Change–Are Governments Prepared? A Cooperative Audit (2012).

2Netherlands Court of Audit, Adaptation to Climate Change: Strategy and Policy (2012).

3GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO-17-317 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 15, 2017).

4Riverside Technology, Inc. and Acclimatise, Climate Risks Study for Telecommunications and Data Center Services (2014).

5GAO, Climate Information: A National System Could Help Federal, State, Local, and Private Sector Decision Makers Use Climate Information, GAO-16-37 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 23, 2015).

6INTOSAI Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Auditing the Government Response to Climate Change: Guidance for Supreme Audit Institutions (June 2010).

7GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

8GAO, Climate Change: Selected Governments Have Approached Adaptation through Laws and Long-Term Plans, GAO-16-454 (Washington, D.C.: May 12, 2016).

9GAO, Climate Change: Better Management of Exposure to Potential Future Losses is Needed for Federal Flood and Crop Insurance, GAO-15-28 (Washington, D.C.: Oct 29, 2014).

10GAO, Federal Supply Chains: Opportunities to Improve the Management of Climate-Related Risks, GAO-16-32 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 13, 2015).

For more information about audits mentioned in this article, please contact: Ms. Michelle Wong at WongM@gao.gov or Ms. Willemien Roenhorst at w.roenhorst@rekenkamer.nl.

[/cmsmasters_text][/cmsmasters_column][/cmsmasters_row]