Civil Society Participation in Audit – the Australian National Audit Office Office’s Approach to Citizen Engagement in Performance Audits

By Isabelle Favre PhD, Senior Director and Daniel Whyte, Audit Principal, Australian National Audit Office

Introduction

In 2017, the INTOSAI Development Initiative (IDI) published the Guidance on Supreme Audit Institutions’ Engagement with Stakeholders, which discusses Supreme Audit Institution (SAI) engagement of citizens and civil society organisations (CSOs), along with other important stakeholder groups, in the audit process. The IDI guide states that ‘SAI engagement with stakeholders at various levels, and with various mechanisms, does lead to greater audit impact’ (IDI 2017, 99–100).

Citizen engagement can occur at several points during an audit: during the planning phase, during the audit proper, during the dissemination of audit reports, or during the follow-up of recommendations. This paper focuses on participation during the audit. It explores some of the approaches that the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) uses to engage with citizens and CSOs during the course of a performance audit, particularly during the fieldwork phase.

The ANAO’s performance audit activities involve audits of the performance of Australian Government programs and entities with focus on assessing economy, efficiency, effectiveness, ethics, and legislative and policy compliance. The ANAO presented 40 performance audits to Parliament in 2021–22 and is planning to increase the number of performance audits it conducts to 48 each year by 2024–25.

ANAO Citizen Contribution Facility

In mid-2013, the ANAO decided to open all in-progress performance audits to input from members of the public through a web-based facility. This decision followed a successful pilot of the initiative, and aligned with broader Australian Government initiatives to promote the use of technology to encourage more open and transparent government, and strengthened community consultation mechanisms.

Through the ANAO website contact page and social media platforms (Twitter, LinkedIn), members of the public are able to provide comments at any time and on any matter, for example to raise concerns with an area of administration or to request that consideration be given to a potential audit topic. The ANAO citizen contribution facility targets contributions that address the objective and the criteria of specific performance audits, and which will be considered as part of the body of evidence collected during the fieldwork stage of audits. In mid-July 2022, 21 performance audits were accepting contributions from members of the public.

Fig 1: The ANAO Website Home Page Offers a Link to the Audits that are Open for Contribution

Source: Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)

The number of contributions collected through the citizen contribution facility varies greatly between audits. Between August 2021 and July 2022, over 1000 contributions were received across 41 performance audits.

Contributions are securely delivered to the relevant audit team, and it is not mandatory for contributors to provide their contact details with their contribution. The Privacy Act 1998 protects the confidentiality of the information gathered through this facility, and information can only be disclosed for purposes defined in the Auditor-General Act 1997 (see Sections 36 and 37), and in line with the ANAO Privacy Policy.

Engaging effectively with citizens

Advertising the audit widely

Performance audit fieldwork generally involves consultation with stakeholders outside the entity being audited. These stakeholders, including CSOs, can be identified through the planning and research stages of the audit. SAIs can then contact CSOs individually to request a meeting or a written submission.

Some audits, for instance audits focusing on service delivery programs, also benefit from a targeted engagement of citizens. In such cases, the ANAO may ask CSOs to advertise the audit to their constituents. Constituents can then use the ANAO’s citizen contribution facility to submit their views independently of the CSO. The audit team may also seek to advertise the audit directly to the citizens affected by the service or program being audited through media outlets, including newspapers and radio.

In a 2019 performance audit, the ANAO conducted fieldwork in the Torres Strait Islands, situated between the northern tip of Australia and Papua New Guinea. The audit team used radio announcements in English and in Torres Strait Creole, an advertisement in the local newspaper, and an interview of the audit manager by a local journalist to encourage local citizens to share their views about the work of government agencies.

Communication clearly and simply

Public awareness of the purpose and work of the ANAO has grown over recent years, mostly due to media coverage following the publication of audit reports. Nevertheless, the majority of citizens do not know or understand the role of the ANAO well. An important step for successful citizen engagement is to make sure that the targeted audience understands why the audit team is seeking citizen input, what type of information is relevant to the audit’s objective, and how the information will be used by the audit team.

Effort is required to present a SAI’s role or the objective of an audit in a clear and simple manner, without misrepresentation or distortion. This is particularly important in communities where people master several languages. In these instances, the ANAO considers the use of translators and interpreters when seeking citizen engagement. In Australia, this can be done professionally and at a cost through the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National), an interpreting service provided by the Australian Government for people who do not speak English and for agencies and businesses that need to communicate with non-English speaking people. It can also be achieved by soliciting the assistance of members of the community. This second option offers less confidence in the quality of the translation, but can be more practical, especially when the ANAO is undertaking fieldwork in rural or remote locations where professional interpreting may have to be conducted by phone. It can also be better aligned with audit budgetary constraints, particularly when consultation is conducted in long meetings and over multiple days.

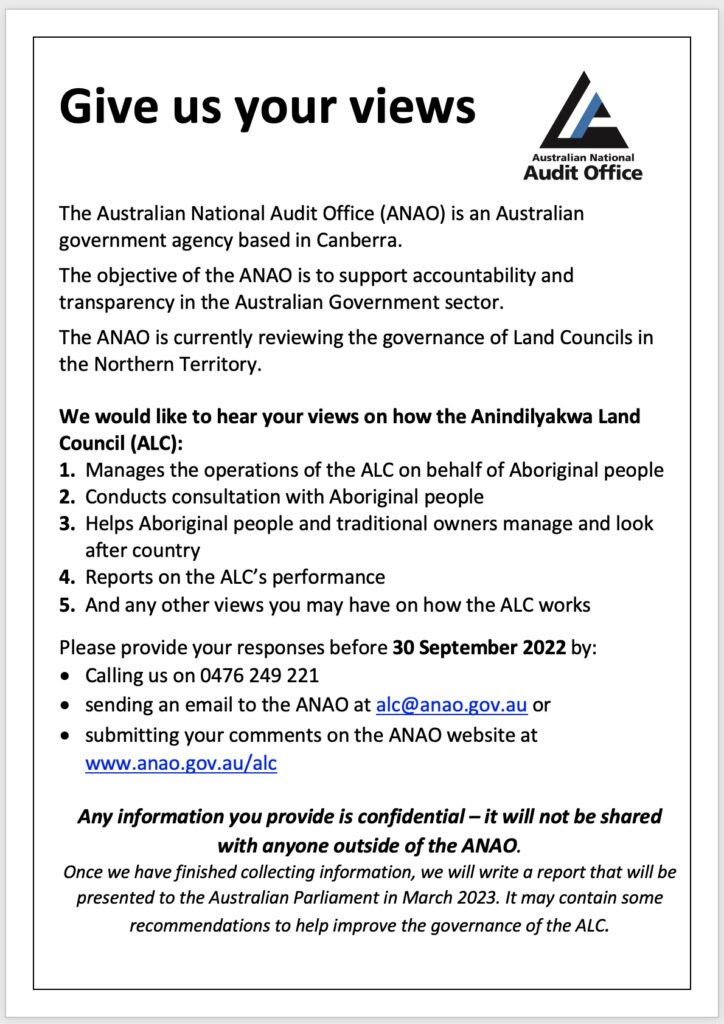

The following example shows the changes that were made to a poster used to seek the views of Aboriginal people living on the Groote Archipelago (located off the coast of Northern Australia) about the governance of the Anindilyakwa Land Council, an organisation assisting Groote Aboriginal people to manage their traditional lands and seas. The picture on the left was developed by the audit team. The picture on the right shows edits suggested by a member of the community accustomed to communicating with Aboriginal people (the local radio coordinator).

Figs 2 and 3: ANAO Audit Team and Community Revised Posters

Source: Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)

Using the information received

Information collected through citizen and CSO engagement can be an important source of evidence in the audit process:

- it provides the audit team with a better understanding of the social and cultural context in which the audited entity operates and delivers services;

- it ensures that the audit focuses on the issues that matter the most to those who are affected by the audited entity’s operations or are the recipients of its services; and

- it allows the audit team to better identify root causes for observed deficiencies.

The ANAO does not usually present information collected through citizen and CSO engagement in a verbatim form in the ANAO audit reports. The ANAO generally uses this information to help identify high-risk areas for the audit, which are then examined and assessed through the analysis of files and documents.

For a 2021 performance audit of the Australian Government’s management of international travel restrictions during COVID-19, the ANAO received 1475 contributions from citizens and CSOs. The audit team reviewed all contributions received and undertook thematic analysis of issues raised to identify high-risk areas for further examination. In particular, contributions were used to identify issues relating to the consistency of travel exemption decision making.

Challenges of citizen engagement

SAIs need to manage several risks when engaging citizens and CSOs in the audit process:

- Managing expectations – Contributors to the audit process sometimes share their views on issues that they would like to see addressed rapidly. They often expect to see a visible improvement in the service they receive or in how the audited entity operates. On average, ANAO performance audits take ten months to complete. It may take many more months for the impact of recommendations and findings to be perceived ‘on the ground’.

- Setting the parameters of performance audit work – The ANAO does not have a role in commenting on the merits of government policy but focuses on assessing the proper use and management of public resources (considering efficiency, effectiveness, economy and ethics) and the implementation of government programs, including the achievement of intended benefits. It is important to establish this fact clearly with citizens and CSOs engaged in the audit process.

- Preserving independence, neutrality and objectivity – The ANAO must manage the risk that citizens or CSOs with views that represent only part of the spectrum of opinions are overrepresented. The ANAO seeks to avoid any perception that the audit team only listened to one side of a debate or were influenced by a specific group of citizens by: aiming to consult as widely as possible within an audit’s time, budgetary and resource constraints; and balancing and corroborating information collected from citizens and CSOs with a rigorous analysis of other sources of evidence.